Most Tuesday evenings on a college campus are full of students studying and preparing for the next day of classes. This past Tuesday, Feb. 4, approximately 70 students and members of the surrounding community gathered in the Johnson Theatre in the Paul Creative Arts Center (PCAC). All ages were represented as they mostly filled the first half of the theater, expectant of the show to come: a free performance from the comedy artist Avner the Eccentric, put on by the College of Liberal Arts’ (COLA) Department of Theatre and Dance.

The laughter, which was effectively unending throughout the approximately 75 minutes Avner the Eccentric performed, complemented the excitement of David Kaye the afternoon before the show. Kaye, a professor of theatre in the department and advisor for a number of other COLA and University of New Hampshire (UNH) programs, studied under Avner early in the 2000s.

“I consider him a mentor and an inspiration for my work,” Kaye said amidst sounds of piano and opera practice from down the hall. He explained that he decided to ask Avner, whose last name is Eisenberg, because of his expertise in comedic performance, likening him to the effect of silent film comedians Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Chaplin and Keaton used physical comedy and its derivative, slapstick comedy.

“He’s a renowned theatre artist… He’s one of the greatest performers in this style of performance,” Kaye said of Eisenberg.

“I teach what he does,” Kaye continued, noting the connection between Eisenberg’s work and the work of Kaye’s “THDA 758: Acting III” students, who have to compose and perform a physical comedy as a final project. With Eisenberg, these students had “a chance to see the master perform,” Kaye said and paused, saying the show Eisenberg aimed to execute succeeds as “both very funny and very profound at the same time.”

Eisenberg has performed “Exceptions to Gravity,” the show’s title, many times before, as confirmed by the online photos of a younger Eisenberg in the same show.

The show’s set was simple: a number of objects rested on a 20-foot long tarp before the show began, from multi-colored bedposts to a table with a red rose, stacks of paper cups and a few objects hidden from view.

The audience was expectant, including Louisa Harless, an employee at nearby Brookdale Spruce Wood Senior Living community. Harless had brought four of her residents as a monthly outing, curious about what the show would contain.

While most theatre shows begin when actors start performing, this show started after the mandatory warnings about fire exits and preventing illegal recordings and ringing phones. “Please do not turn off your cell phones,” Eisenberg’s recorded voice said. “This is only theatre… and you wouldn’t want to miss an important call.”

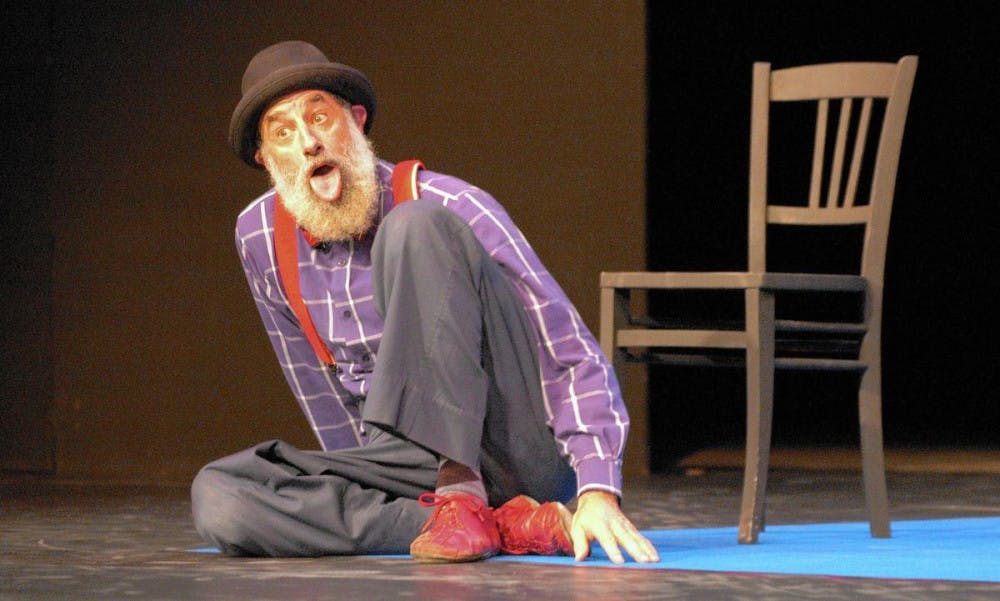

The performance began with Eisenberg emerging from stage right – the audience’s left – and immediately the antics started as Eisenberg’s character struggled to sweep the stage with a push broom that fell apart, but not until he had tried to light a cigarette, dropped the cigarettes and matches and burned his finger with a lit match.

Eisenberg learned the skills on display from Jacques Lecog, a comedy performer in Paris, “who launched this style of performance,” according to Kaye. Eisenberg’s online biography also cited comedy performer Carlo Mazzone-Clementi as fundamental to his performance education.

Kaye synthesized Eisenberg’s performance style: “He creates a performance that is highly structured and rehearsed, (but also) interactive with the audience.”

Five minutes into the show, Eisenberg broke the fourth wall and would continuously do so, from exasperated expressions – he never spoke – to coming off the stage and into the audience, poking fun at everyone from late arrivals to a student he had prepared with a disposable camera, who took a disruptive flash photo midway through the show. Eisenberg wrote out a tardy slip for the late arrivals and took the student’s camera, taking pictures from various angles of the audience before returning it wrapped in an informational pamphlet about a UNH program and in a bag he’d given to the student. The bag contained two rolls of toilet paper.

These antics filled much of the performance but occurred before Eisenberg’s show even started; Eisenberg eventually held up a small banner that read “Show Starts in 5 minutes.”

In response, Eisenberg’s character checked his pocket watch, left, confirmed the time with a bigger clock, and pulled out a box of popcorn—from his pants, held up by red suspenders.

He joked with the popcorn, catching it in his mouth – sometimes – and giving popcorn to members of the audience in the first row of seats. Anyone in those seats, and later the second row, was fair game for Eisenberg to interact with, including a woman who was hesitant to take his popcorn. Thus, he bopped the fedora he wore upside down, pushing the top part in to imitate the cap of a Catholic Cardinal, made the sign of the cross, and gave it to her as if he was giving Communion.

The audience was rapt the entire performance. Eisenberg’s jokes ran the gamut from silly to suggestive innuendos to slight-of-hand and balancing objects – including a ladder – on his chin. Well into the “actual” show, the audience cheered and applauded after he balanced the ladder as Eisenberg played with the cheers like a classical music conductor. Miming a conductor and the conductor’s stand, he created a small audience performance of cheers and whistles of varying octaves and volumes. He ended it with the entire audience rising and some bowing toward the stage.

Eisenberg’s performance was supported by a fund used to create the UNH Celebrity Series, Kaye said. The Celebrity Series brought various performers, from world-renowned musicians to famous puppeteers, to UNH. Admission was not free, but tickets were at a reduced price from that expected of a private performance hall; student tickets were only $10.

Kaye explained that the Celebrity Series had been first developed to bring famous performers to the Seacoast, as “UNH used to be the only place to see [these shows] in the area.” That niche has been filled by other institutions, such as the Music Hall in nearby Portsmouth, and combined with the cost of the Celebrity Series, its last show was in spring 2018.

Yet, the Department of Theatre and Dance has some funds from the endowment that still allow for occasional shows from “world-renowned performers,” Kaye said. This fund paid Eisenberg.

“We can’t bring in the number of performances that we did under the Celebrity Series,” Kaye said. The fund has also changed to fit a more academic purpose. With a “tradeoff” of less performers with a no-cost show, the performers often help students learn their craft.

“The purpose of the funding is earmarked toward students in the performing arts… it is utilized to expand their exposure to artists,” Kaye said. Kaye and Eisenberg are coordinating a workshop for the students in the department led by Eisenberg.

Eisenberg even worked with students after the show, advising student stagehands and light operators on packing up equipment of a traveling show.

The performance finished with two standing ovations from most of the audience—two because after the first, the show wasn’t done.

The show’s finale was the official “show” Avner’s character was playing in, where he ate 15 paper napkins and expelled them as a rope of napkins, akin to the popular magic trick, and then as a bouquet.

After the performance, many members of the audience came to the stage to speak with Eisenberg and express appreciation for his performance. A young boy asked for his autograph and the student with the disposable camera asked for a photo. At that point, Eisenberg retrieved his cell phone to show a couple of the many photos he’d taken with his audience.

“I don’t think it could have gone better… Except I couldn’t catch the popcorn. But it doesn’t really matter,” Eisenberg said with a grin when asked how he felt the show went.

“(The show) was wonderful…I was very, very happy with all of it.”