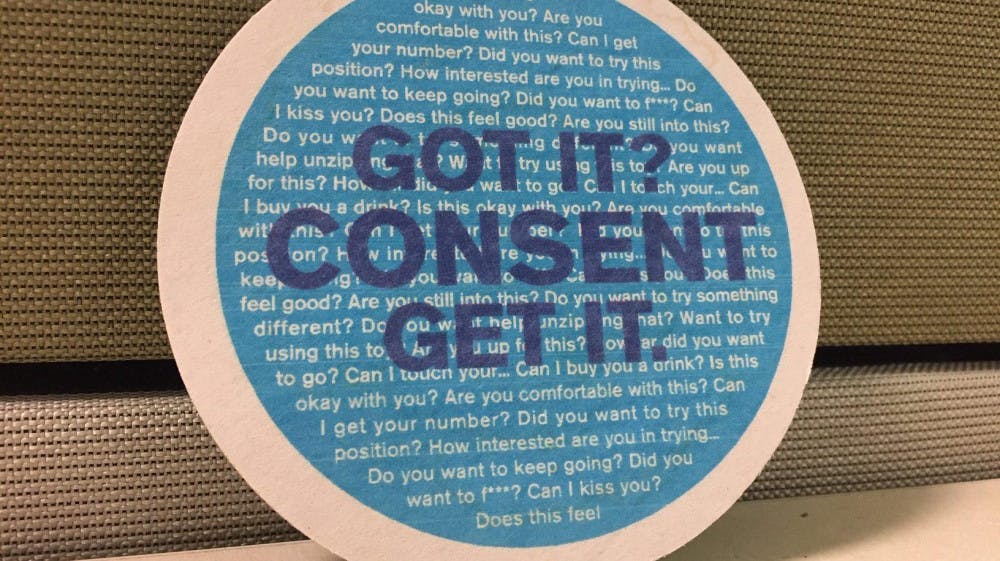

On your next trip to Libby’s Bar and Grill in downtown Durham, you may notice a different type of message being advertised on your coaster. It’s not the typical beer promo, vodka ad, or even awareness about the dangers of drinking and driving. Instead, you will see a coaster detailing the many ways in which a person can obtain consent in a bar environment.

These coasters are a few of the many ways that the Sexual Harassment and Rape Prevention Program (SHARPP) are spreading the message of getting consent.

“Consent should be present there too,” SHARPP Outreach and Training Coordinator Erica Vazza said. “When we know students are active and drinking in those spaces and we want to get them thinking about this before the situation turns into something different.”

A common misconception that students tend to have, according to Vazza, is that they think consent is a formal process, but that is not true in most cases.

“Everyday communication is consensual,” she said. “When I ask you if I can borrow $20, that’s consent. It’s as simple as that.”

Located on the edge of the University of New Hampshire (UNH) campus, SHARPP provides free services and that are designed to not only spread awareness and educate the campus, but to also help students work through a nonconsensual sexual experience.

The first 6 to 8 weeks of a first-year college student’s experience is what’s known as the “Red Zone” and about 50 percent of all cases of sexual violence reported on campus happen within these beginning weeks. UNH is no exception to this statistic. According to research conducted by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), sexual assault is the crime that is most likely to be committed on a college campus and is often than not reported to the university police.

Vazza says this time of year is crucial to “push the consent message” and target as many students as she can. During June orientation and various other tabling opportunities, SHARPP is always there spreading awareness about consent.

“We do a lot of programming around first-year students specifically,” SHARPP Prevention Specialist Zachary Ahmed-Kahloon said.

Per Vazza, a lot of the time, first-year students are not coming in with the right understanding of consent, and that is due to many high schools not having standardized policies on requiring that type of education. In high school and perhaps even earlier, students are already dating or engaging in intimate relationships, but they are not being taught consent.

“We don’t try to attack the problem earlier,” said Samantha Percuoco, a client services advocate at Haven. “It puts a lot of pressure on college campuses.” Percuoco, a senior psychology and justice studies major at UNH, said that during her first year she learned that silence means no. She did not receive any type of consent education until her first semester at UNH.

Haven, the crisis center for the seacoast, provides educational programs to K-12 schools, but in order to do so the schools must request the program.

Vazza says that children should be learning who to tell and how to tell someone about an experience that they know was not consensual. But many children are not receiving this knowledge.

“How do young kids know that not everyone their age is experiencing this type of behavior?” she said.

SHARPP’s involvement on campus hopes to break the barrier surrounding the conversations involving consent. They aim to educate while also providing confidential advocacy to survivors of sexual violence. While it’s not always easy to talk about sexual violence, it’s important to know the ways in which someone can prevent it, and that may start with a coaster at a local bar.