“Travel with me across the sea,” Dr. Tricia Peone said to an enraptured audience of students and visitors alike. For the next 15 minutes, her portion of a longer lecture, Dr. Peone would paint an image of Puritan New England and its religious culture, as well as her favorite topic: witchcraft.

For Dr. Peone, the Puritan colonial era is one of the most fascinating. With a Ph.D. in history from the University of New Hampshire (UNH), her main area of expertise is witchcraft and witch trials in New England. Her presence at the lecture entitled ‘Historical Perspectives on Witch Trials from Germany to New England and the Due Rights Process of the Accused’ held Oct. 19 in Horton Hall was necessary.

While her focus is generally on New England witch trials, New Hampshire-specific trials carry a special interest. This is largely because she is from New Hampshire herself, but also because the New Hampshire ones garner less attention than others. It is her eventual goal to write a book about the New Hampshire witch trials, which would be the first of its kind.

“They believed in an invisible world just as much as a physical world,’ Dr. Peone said, explaining how Puritan settler's mindset enabled the New Hampshire trials to happen in the first place. “They also thought the new world was Satan’s realm so they had expectations of magical creatures in New England.”

This complex view of New England and the world settlers lived in meant magic, both good and evil, was something very real.

So-called “good magic” was usually accepted by local people. They would use certain plants to ward off evil spirits, carve runes for protection and predicted marriages. But it was when this magic had bad results that accusations of witchcraft were tossed around.

No one was actually executed for witchcraft in New Hampshire, a fact that Dr. Peone shared with pride. But there certainly were people accused, some who had these accusations impact the rest of their lives. One such person is the locally famous Eunice Cole of Hampton, New Hampshire.

Eunice Cole (also called Goody Cole) was accused multiple times by various members of her community between 1656 and 1680. She was accused of everything from killing cows to enticing children, but Dr. Peone said her true crime was simply being unlikeable.

“People said she grumbled. They said she cursed people. She was just grumpy basically,” she said. “She once bit a constable's ear when (they) came to investigate about accusations of stealing pigs.”

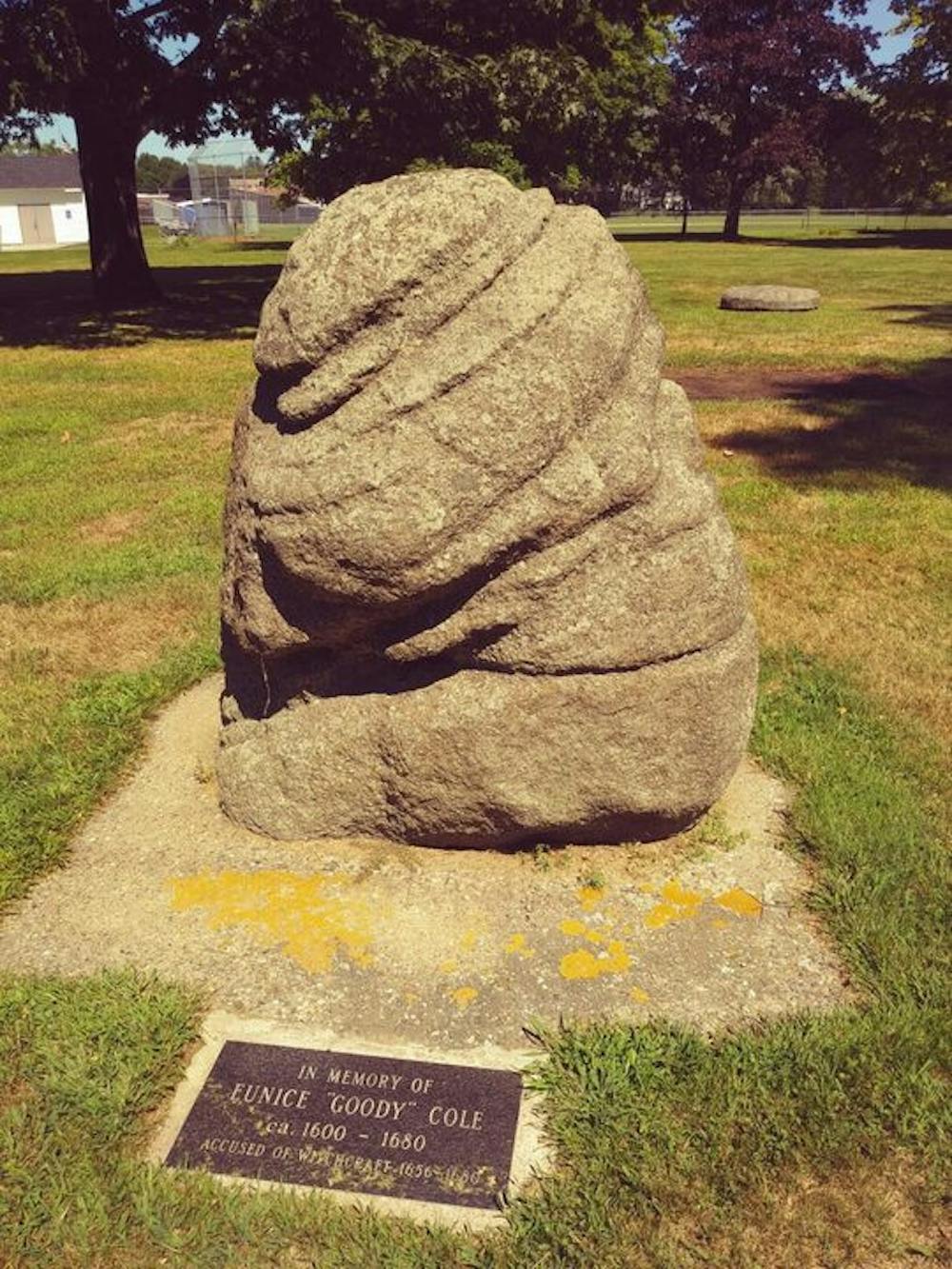

Not a single one of the members of her community came forward to defend her when she was accused, even her husband. But ultimately the court ruled there simply was not enough evidence to convict her. With the constant accusations, Eunice Cole was constantly bouncing between Hampton and incarceration in Boston before being acquitted. She died under what was essentially house arrest in 1680. She was later exonerated by the city of Hampton in the 1930s, and now has a memorial in the city

Another well-known accusee was Rachel Fuller, also of Hampton. She was accused of witchcraft in 1680 after a local child died. Apparently, Fuller had visited the child prior to the death and acted quite strangely during her visit. She subsequently was brought to Dover for trial and was held in jail with a 100-pound bond. But the court decided to release her, and she was later acquitted of all charges.

As for the due process aspect, J. Kirk Trombly, a practicing lawyer and UNH Justice Studies professor, spoke at the lecture. He posited that Puritan’s theocratic, or church-run, government contributed immensely to the hysteria surrounding potential witchcraft. Citations from the bible were in their law books, and every trial began with prayer, he said.

But it wasn’t just the religious aspect that created an environment that allowed witch trials to happen. People had minimal rights when accused, as they were seen guilty until proven innocent. There was no freedom of speech or right to an attorney in this time, and modern hearsay laws, which say gossip cannot be used as evidence, did not apply. Instead “spectral evidence” was a key factor, permitting anecdotes from visions as valid testimony. If someone said they had a vision that another person was a witch, it was justifiable in the court’s eyes.

This lack of proper due process combined with the Puritan worldview made Colonial New England the perfect storm for witch accusations. Compared to Salem’s witch trials, though, New Hampshire’s seem to pale in comparison. The New Hampshire courts seemed entirely unwilling to convict people of witchcraft, especially compared to their counterparts in other states.

Dr. Peone believes there are multiple reasons New Hampshire was so mild.

“New Hampshire was a little less Puritan than Massachusetts,” said Dr. Peone. “Some of the people who came to New Hampshire specifically came here in the 17th century after having lived in Massachusetts and didn’t get along with the Puritan authority there.”

They were still Puritans, Dr. Peone said, but their disagreements with other Puritan communities might have led to them not following the Puritan doctrine as intensely. This might have contributed to the unwillingness to convict accused witches.

Whatever it may have been, New Hampshire did not fall down the same hole Massachusetts did when it came to witch trials and came out of the 17th century with a few accusations and indictments but little more.

“The 17th century is a lot different than today, but people are essentially still the same,” Dr. Peone said. “It tells us what could happen in a community (where) someone is hated, and seen as a target for frustration and anger.”

For Dr. Peone, the Puritan colonial era is one of the most fascinating. With a Ph.D. in history from the University of New Hampshire (UNH), her main area of expertise is witchcraft and witch trials in New England. Her presence at the lecture entitled ‘Historical Perspectives on Witch Trials from Germany to New England and the Due Rights Process of the Accused’ held Oct. 19 in Horton Hall was necessary.

While her focus is generally on New England witch trials, New Hampshire-specific trials carry a special interest. This is largely because she is from New Hampshire herself, but also because the New Hampshire ones garner less attention than others. It is her eventual goal to write a book about the New Hampshire witch trials, which would be the first of its kind.

“They believed in an invisible world just as much as a physical world,’ Dr. Peone said, explaining how Puritan settler's mindset enabled the New Hampshire trials to happen in the first place. “They also thought the new world was Satan’s realm so they had expectations of magical creatures in New England.”

This complex view of New England and the world settlers lived in meant magic, both good and evil, was something very real.

So-called “good magic” was usually accepted by local people. They would use certain plants to ward off evil spirits, carve runes for protection and predicted marriages. But it was when this magic had bad results that accusations of witchcraft were tossed around.

No one was actually executed for witchcraft in New Hampshire, a fact that Dr. Peone shared with pride. But there certainly were people accused, some who had these accusations impact the rest of their lives. One such person is the locally famous Eunice Cole of Hampton, New Hampshire.

Eunice Cole (also called Goody Cole) was accused multiple times by various members of her community between 1656 and 1680. She was accused of everything from killing cows to enticing children, but Dr. Peone said her true crime was simply being unlikeable.

“People said she grumbled. They said she cursed people. She was just grumpy basically,” she said. “She once bit a constable's ear when (they) came to investigate about accusations of stealing pigs.”

Not a single one of the members of her community came forward to defend her when she was accused, even her husband. But ultimately the court ruled there simply was not enough evidence to convict her. With the constant accusations, Eunice Cole was constantly bouncing between Hampton and incarceration in Boston before being acquitted. She died under what was essentially house arrest in 1680. She was later exonerated by the city of Hampton in the 1930s, and now has a memorial in the city

Another well-known accusee was Rachel Fuller, also of Hampton. She was accused of witchcraft in 1680 after a local child died. Apparently, Fuller had visited the child prior to the death and acted quite strangely during her visit. She subsequently was brought to Dover for trial and was held in jail with a 100-pound bond. But the court decided to release her, and she was later acquitted of all charges.

As for the due process aspect, J. Kirk Trombly, a practicing lawyer and UNH Justice Studies professor, spoke at the lecture. He posited that Puritan’s theocratic, or church-run, government contributed immensely to the hysteria surrounding potential witchcraft. Citations from the bible were in their law books, and every trial began with prayer, he said.

But it wasn’t just the religious aspect that created an environment that allowed witch trials to happen. People had minimal rights when accused, as they were seen guilty until proven innocent. There was no freedom of speech or right to an attorney in this time, and modern hearsay laws, which say gossip cannot be used as evidence, did not apply. Instead “spectral evidence” was a key factor, permitting anecdotes from visions as valid testimony. If someone said they had a vision that another person was a witch, it was justifiable in the court’s eyes.

This lack of proper due process combined with the Puritan worldview made Colonial New England the perfect storm for witch accusations. Compared to Salem’s witch trials, though, New Hampshire’s seem to pale in comparison. The New Hampshire courts seemed entirely unwilling to convict people of witchcraft, especially compared to their counterparts in other states.

Dr. Peone believes there are multiple reasons New Hampshire was so mild.

“New Hampshire was a little less Puritan than Massachusetts,” said Dr. Peone. “Some of the people who came to New Hampshire specifically came here in the 17th century after having lived in Massachusetts and didn’t get along with the Puritan authority there.”

They were still Puritans, Dr. Peone said, but their disagreements with other Puritan communities might have led to them not following the Puritan doctrine as intensely. This might have contributed to the unwillingness to convict accused witches.

Whatever it may have been, New Hampshire did not fall down the same hole Massachusetts did when it came to witch trials and came out of the 17th century with a few accusations and indictments but little more.

“The 17th century is a lot different than today, but people are essentially still the same,” Dr. Peone said. “It tells us what could happen in a community (where) someone is hated, and seen as a target for frustration and anger.”