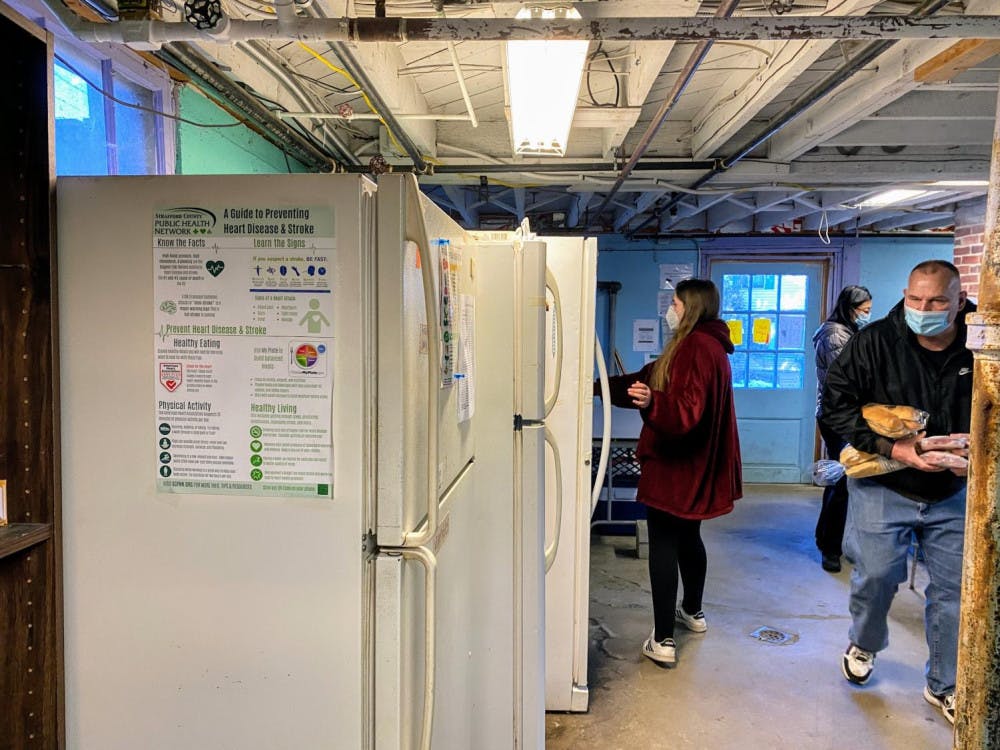

Durham, NH— John* walks to the Waysmeet Center food pantry every Friday. It’s the only weekday the University of New Hampshire (UNH) student isn't stuck in labs or classes that sometimes don’t get out until 9 p.m. As John enters the parking lot a volunteer rushes out to meet him. They carry a cardboard box filled with food. Patrons used to be able to pick out their groceries themselves, but that was before the pandemic.

John transfers the food into bags to make the journey back to his residential hall easier. On Saturday, he’ll spend all day in his hall’s kitchen cooking his meals for the week. The rest will come from the African market in Manchester or his friend’s extra meal swipes for the UNH’s dining hall.

Food insecurity is an issue that has been exacerbated by the pandemic. During the 2017-2019 period, an estimated 6.6% of households in New Hampshire were food insecure. The New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI) expects this number to increase to levels potentially greater than those experienced during the Great Recession because of the economic instability caused by the pandemic.

These conditions have worsened in recent months due to the omicron variant, record-high inflation, supply chain delays, labor shortages and the housing crisis.

“More than half of my stipend goes to housing,” said John. He’d been trying for months before he left his home country of Nigeria to secure an apartment in New Hampshire, but everywhere was full. “At some point, I was like, ‘I don't know anyone here. I can’t just come around. There’s no place to stay.’”

John had been drawn to UNH for its research facility as most of his previous projects in Nigeria had been dropped due to a lack of funds. Nigerian colleges just didn’t get the research money that American universities did.

So, John applied for UNH’s on-campus housing, leaving most of his remaining stipend to cover school supplies.

Saint Thomas More Parish’s food pantry coordinator Cindy Racic also reported an uptick in people using their services in recent weeks, which she in part attributes to the end of government Covid-19 assistance. Patrons at the Waysmeet Center and Saint Thomas More Parish also identified rising gas and grocery prices as main causes of their food insecurity.

“It’s hard to have to come here. It really is. I almost feel like I want to hide away because I think a professor might see me or something,” said a Waysmeet patron, who wished to be kept anonymous. “I don’t know how other people survive.”

Inflation has also made it more difficult for food pantries to supply their users with fresh produce and meat as many people no longer have the disposable income to purchase and donate these items. The Waysmeet Center’s Food Rescue program, which has volunteers rescue items close to shelf date from local grocery stores, has allowed them to avoid reliance on just donations. However, they too are feeling the hit to their meat supply.

The price of beef, pork and poultry make up a quarter of the food price increases. In addition, over 59,000 meat sector workers have been infected and 300 died since the pandemic began which further contributes to labor shortages and delays in production.

“We have a shortage of ability to move goods. And that is across the board,” said Wendy Pothier, a UNH associate professor and business and economics librarian. Supply chain issues are typically local with weather conditions or strikes causing delays, but because the global community had been continuously dealing with coronavirus there’s been no time to catch up. This has caused backups all along the supply chain from shipping containers to trucker shortages.

Pothier explained the omicron variant also presents new challenges as more people are getting sick amidst the United States’ efforts to reopen.

“Companies aren't hurting in this scenario. It’s people,” said Pothier. “It's people putting things on pallets. It's people putting things on trucks. It’s people filling containers. And people are getting sick, people are getting hurt, and people have bodies that can only have so much capacity to lift and move things.”

Pothier’s sentiment regarding humanness is echoed in Waysmeet’s mission statement. The center has no restrictions on who can use their services. Patrons don’t even have to live in the state with one recent user driving up from Connecticut.

“At the end of the day, everyone is entitled to food. That's a basic necessity. So, to ask questions, or to make requirements for people to come to our food pantry, will take away from serving the whole community,” said Food Pantry Coordinator Kierra Hulan.

Hulan is working at Waysmeet as part of her senior social work internship. Like John, she is no stranger to hunger. The 21-year-old student grew up in Nashua as one of three kids with a clinical social work mother and an in-and-out of work father. Yet, despite there being only one steady source of income they still made too much to qualify for food stamps. Hulan’s mother, a devout Christian, turned to local church pantries for support but income restrictions kept the family from getting the amount of food they needed.

“There were times when we just didn't have enough money to be able to get food. And we really truly relied on eating at school,” she recalled. But school was its own challenge as Hulan struggled to focus past her hunger. “There was a lot more focus on surviving and a lot less focus on becoming who I am today.”

While there is no clear way out of food insecurity and its effects can linger for many who experience it, John is one of the few who sees an eventual end to his situation.

He is working towards a new apartment next summer which he says would save him around $400 a month on housing, and he won’t need to use Waysmeet anymore.

“I think that will help me a lot,” said John. “Probably my [new] situation can also get access to food.”

*name changed to protect anonymity

John transfers the food into bags to make the journey back to his residential hall easier. On Saturday, he’ll spend all day in his hall’s kitchen cooking his meals for the week. The rest will come from the African market in Manchester or his friend’s extra meal swipes for the UNH’s dining hall.

Food insecurity is an issue that has been exacerbated by the pandemic. During the 2017-2019 period, an estimated 6.6% of households in New Hampshire were food insecure. The New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI) expects this number to increase to levels potentially greater than those experienced during the Great Recession because of the economic instability caused by the pandemic.

These conditions have worsened in recent months due to the omicron variant, record-high inflation, supply chain delays, labor shortages and the housing crisis.

“More than half of my stipend goes to housing,” said John. He’d been trying for months before he left his home country of Nigeria to secure an apartment in New Hampshire, but everywhere was full. “At some point, I was like, ‘I don't know anyone here. I can’t just come around. There’s no place to stay.’”

John had been drawn to UNH for its research facility as most of his previous projects in Nigeria had been dropped due to a lack of funds. Nigerian colleges just didn’t get the research money that American universities did.

So, John applied for UNH’s on-campus housing, leaving most of his remaining stipend to cover school supplies.

Saint Thomas More Parish’s food pantry coordinator Cindy Racic also reported an uptick in people using their services in recent weeks, which she in part attributes to the end of government Covid-19 assistance. Patrons at the Waysmeet Center and Saint Thomas More Parish also identified rising gas and grocery prices as main causes of their food insecurity.

“It’s hard to have to come here. It really is. I almost feel like I want to hide away because I think a professor might see me or something,” said a Waysmeet patron, who wished to be kept anonymous. “I don’t know how other people survive.”

Inflation has also made it more difficult for food pantries to supply their users with fresh produce and meat as many people no longer have the disposable income to purchase and donate these items. The Waysmeet Center’s Food Rescue program, which has volunteers rescue items close to shelf date from local grocery stores, has allowed them to avoid reliance on just donations. However, they too are feeling the hit to their meat supply.

The price of beef, pork and poultry make up a quarter of the food price increases. In addition, over 59,000 meat sector workers have been infected and 300 died since the pandemic began which further contributes to labor shortages and delays in production.

“We have a shortage of ability to move goods. And that is across the board,” said Wendy Pothier, a UNH associate professor and business and economics librarian. Supply chain issues are typically local with weather conditions or strikes causing delays, but because the global community had been continuously dealing with coronavirus there’s been no time to catch up. This has caused backups all along the supply chain from shipping containers to trucker shortages.

Pothier explained the omicron variant also presents new challenges as more people are getting sick amidst the United States’ efforts to reopen.

“Companies aren't hurting in this scenario. It’s people,” said Pothier. “It's people putting things on pallets. It's people putting things on trucks. It’s people filling containers. And people are getting sick, people are getting hurt, and people have bodies that can only have so much capacity to lift and move things.”

Pothier’s sentiment regarding humanness is echoed in Waysmeet’s mission statement. The center has no restrictions on who can use their services. Patrons don’t even have to live in the state with one recent user driving up from Connecticut.

“At the end of the day, everyone is entitled to food. That's a basic necessity. So, to ask questions, or to make requirements for people to come to our food pantry, will take away from serving the whole community,” said Food Pantry Coordinator Kierra Hulan.

Hulan is working at Waysmeet as part of her senior social work internship. Like John, she is no stranger to hunger. The 21-year-old student grew up in Nashua as one of three kids with a clinical social work mother and an in-and-out of work father. Yet, despite there being only one steady source of income they still made too much to qualify for food stamps. Hulan’s mother, a devout Christian, turned to local church pantries for support but income restrictions kept the family from getting the amount of food they needed.

“There were times when we just didn't have enough money to be able to get food. And we really truly relied on eating at school,” she recalled. But school was its own challenge as Hulan struggled to focus past her hunger. “There was a lot more focus on surviving and a lot less focus on becoming who I am today.”

While there is no clear way out of food insecurity and its effects can linger for many who experience it, John is one of the few who sees an eventual end to his situation.

He is working towards a new apartment next summer which he says would save him around $400 a month on housing, and he won’t need to use Waysmeet anymore.

“I think that will help me a lot,” said John. “Probably my [new] situation can also get access to food.”

*name changed to protect anonymity