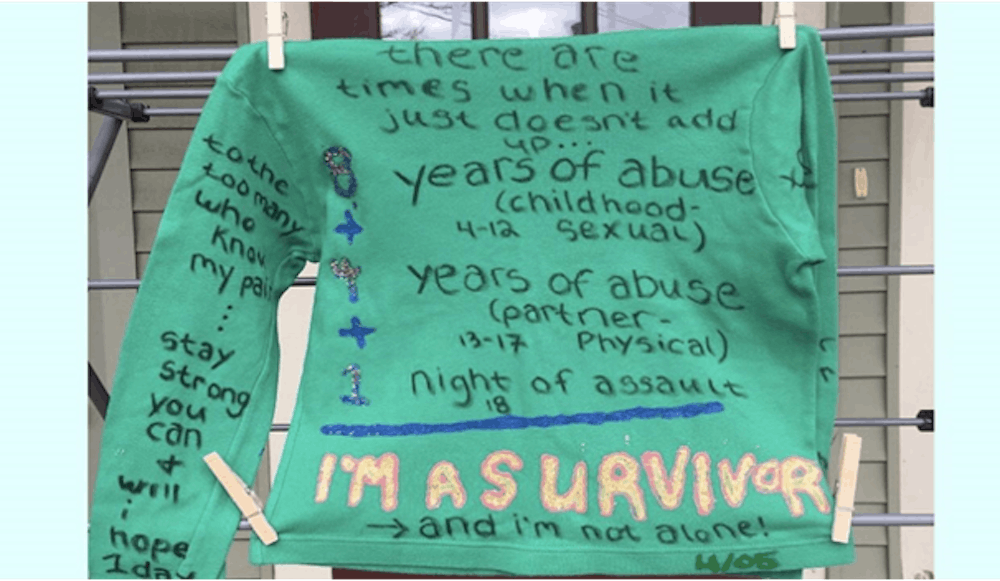

[DURHAM, NH]-- Since 1990, the Clothesline Project has brought awareness to the issue of violence against men, women and children. For those who have been affected by violence, the Clothesline Project allows them to express their emotions on a t-shirt. To raise awareness of sexual assault, sexual harassment and domestic violence, the Sexual Harassment & Rape Prevention Program (SHARPP) at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) dedicated a couple days to their own Clothesline Project. Between social media, coordination and strength from survivors in Durham, this project was able to raise awareness to some of the most impactful issues within society.

SHARPP has been in place at UNH since 1978 and has spent the past 43 years helping survivors. From their outreach initiatives, campaigns and events, their program at UNH not only educates students, faculty and staff, but also any array of services for survivors. For SHARPP, the Clothesline Project has been incorporated in several events, a few times a year. This week’s Clothesline Project was to encapsulate Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Within the month of April, social media has been filled with the importance of consent, survivors of assault and serious statistics surrounding these issues. According to the National Sexual Violence Research Center (NSVRC), one in five women and one in 16 men are sexually assaulted while in college alone. With around 15,000 students attending UNH, this estimate would translate and predict that predict that approximately 1500 women and 468 men would be assaulted. Nonetheless, SHARPP has been there for every survivor who feels ready to reach out for help.

Previous members of AmeriCorps have joined SHARPP to promote advocacy and give survivors a safe place. Julia Kelley-Vail has been working for SHARPP for the past almost three years. An alumni of UNH carrying her master’s in social work, Kelley-Vail valiantly takes on her job at SHARPP as the direct services coordinator, training volunteers. “We need to bring voices to the university,” Kelley-Vail said.

Kelley-Vail has trained volunteers like Isaiah Chisholm, who is now a staff advocate and first responder. With two pools of volunteers, Chisholm works under the 24-hour, direct communication with survivors and is one of 19 other volunteers. Kelley-Vail and Chisholm have always held an important urge to help bring awareness to sexual assault and be active members of the community. The Clothesline Project is one way this is accomplished.

Because this is an annual activity for SHARPP, there are hundreds of shirts to sort through on top of the news ones that typically come in. The coronavirus (COVID-19) restricted SHARPP from making new shirts this year, however, there was no reason to not honor previously told stories of survivors. COVID-19 also made it difficult to leave the shirts up for the whole week, as the university didn’t want large gatherings to view the display. SHARPP also likes an advocate to sit by the shirts in case any story may be reactivating or traumatic for those reading them, but COVID-19 made that assistance unavailable this year.

There is always a level of cautiousness that needs to be taken when putting these shirts up. These shirts represent someone’s story and a personal piece of their life. As promotional as it may be to leave the shirts up all year, there is always a chance of vandalism, Chisholm said.

The stories on these t-shirts are not the only effect that lasts within the community or SHARPP alone - it’s the number of stories. “Sometimes I look at the magnitude [of stories] and how far back they go. When I pick up a box of shirts, it’s almost 40 pounds. It’s inspiring and saddening,” Chisholm said.

The Clothesline Project helps reveal for how long and often these things are happening. Kelley-Vail adds that SHARPP has been collecting shirts since the ‘90s.

Despite the mass number of shirts SHARPP holds, it’s important to highlight those who haven’t come forward to make a shirt. Chisholm makes a point that even though there are all of these stories being displayed, there are also several stories that haven’t been told. NSVRC also notes that more than 90% of sexual assault victims on college campuses do not report the assault.

There is power in educating yourself, and with the Clothesline Project, viewers learn one of two things: there are millions of people who’ve had to survive and that there is an oppressive part of society that makes it difficult for the remainder of those survivors to write out their story. “If I’m thinking about it from a community perspective, [students] are here for a few years and move on. But [the community] sees it constantly changing. I hope that helps people feel less isolated and feel safe and can reach out when ready,” Chisholm said.

Kelley-Vail resonates with the support the Clothesline Project gives to survivors. They can see that they’re not alone and the community is there for them. The Durham community has been able to value the power of interpersonal connections and realize how much of a reality sexual assault is, even in their own town. However, SHARPP wants the community to know they can be a part of ending this violence.

The Clothesline Project makes an empowering statement, as the overwhelming wave of sadness also prevails hope and healing to these survivors. “[The Clothesline Project] is a part of our history as an organization, community and university,” Chisholm said.

SHARPP provides a 24/7 Helpline: 603-862-7233

OR a Text line (Mon.-Fri. 9 a.m.-4 p.m.): 603-606-9393

Visit their website: https://www.unh.edu/sharpp/

Photo courtesy of @unhsharpp Instagram. April 14, 2021.