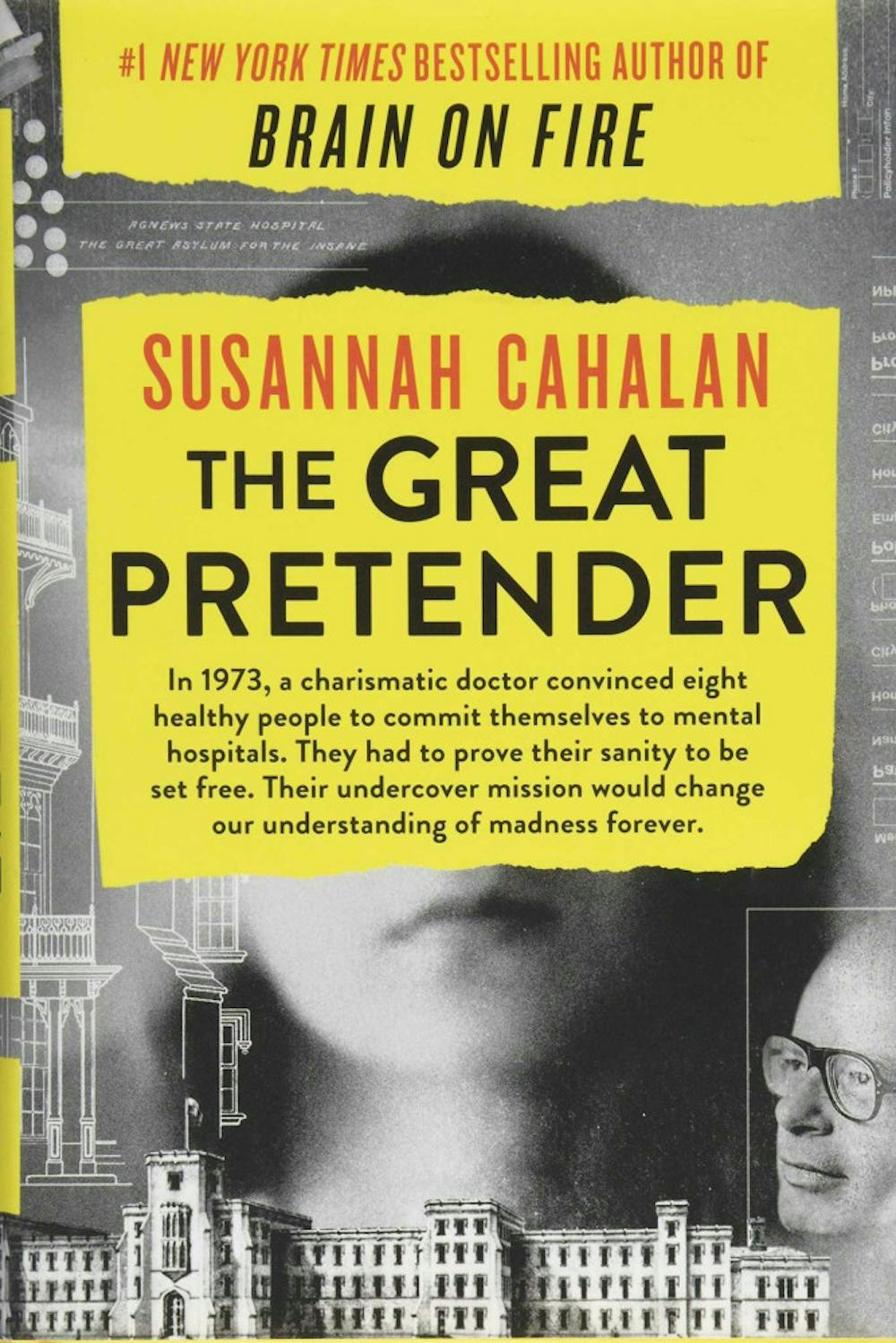

Susannah Cahalan, known for her memoir “Brain on Fire,” had a brush with psychosis when she developed a rare autoimmune disorder, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. She believed she could age people with her mind and read nurses’ thoughts. Her first book, “Brain on Fire,” details her descent into madness and what it was like not being in control of her body with no one to help. In her new book, “The Great Pretender,” Cahalan marries her own experience with psychosis with an experiment posed by American psychologist David Rosenhan. The Rosenhan experiment asked the question, "Can psychiatrists tell the sane from the insane?" One quote from Cahalan that I loved was, “We were mastering the great mysteries of the world-conquering space, cancer, and infertility. But we still couldn't properly answer this question: what is a mental illness? Or better yet, what isn't?” Along with Rosenhan’s experiment, this was the guiding question for the book.

Rosenhan’s study involved himself and eight other volunteers who went undercover in psychiatric wards in the 1970s. From this research, Rosenhan concluded that doctors actually had no idea what they were doing and their practice was all a big guessing game. This study led to the closing of hundreds of psychiatric hospitals and the creation of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, also known as the DSM (or the edition we use today, the DSM-5.) Since this is a memoir, she does not romanticize mental illness or downplay what she went though. She even writes, “Mental illness was cinematic: the genius mathematician John Nashz played by Russell Crowe in ‘A Beautiful Mind,’ drawing equations on chalkboards, or a sexy borderline à la Angelina Jolie in ‘Girl, Interrupted.’ It seemed almost aspirational, some kind of tortured but sophisticated private club.” She makes it clear that mental illness, her or otherwise, isn’t something to strive for but rather something dark and terrible to go through.

Throughout the book, Cahalan points out the pros and cons of nearly every decision made from this study. This includes who was involved, why Rosenhan got so involved, why certain facilities were chosen, the time spent at each facility, the way Rosenhan took his notes, among a variety of other variables. All the names of the participants were changed, so no one truly knows who participated in the study other than the brief descriptions that accompanied their fake names, although who is to say if they were fake too? As she delves deeper into this borderline obsession with the study, she soon makes a shocking discovery.

Although the book can read as a bit academic at times, it’s extremely well organized and well researched (there are over 90 pages of sources on the back of my copy). There is so much rich history throughout the book as well, from Nellie Bly's undercover mission and how these patients were being treated to Rosemary Kennedy being lobotomized and the history of over-diagnosing, which all gives the reader a deeper understanding of the growth and consequences of psychology and psychiatry. She seems to come to a controversial conclusion—no one knows what psychiatry is or how the brain and the body are linked. “For every miracle like me,” she writes, “there are a hundred like my mirror image; a thousand rotting away in jails or abandoned on the streets for the sin of being mentally ill; a million told that it's all in their heads.”

Anyone interested in psychology, medicine or history will love this book!